If you are looking for the newer version of this post it’s here.

Category: updates

Sabbatical reflections

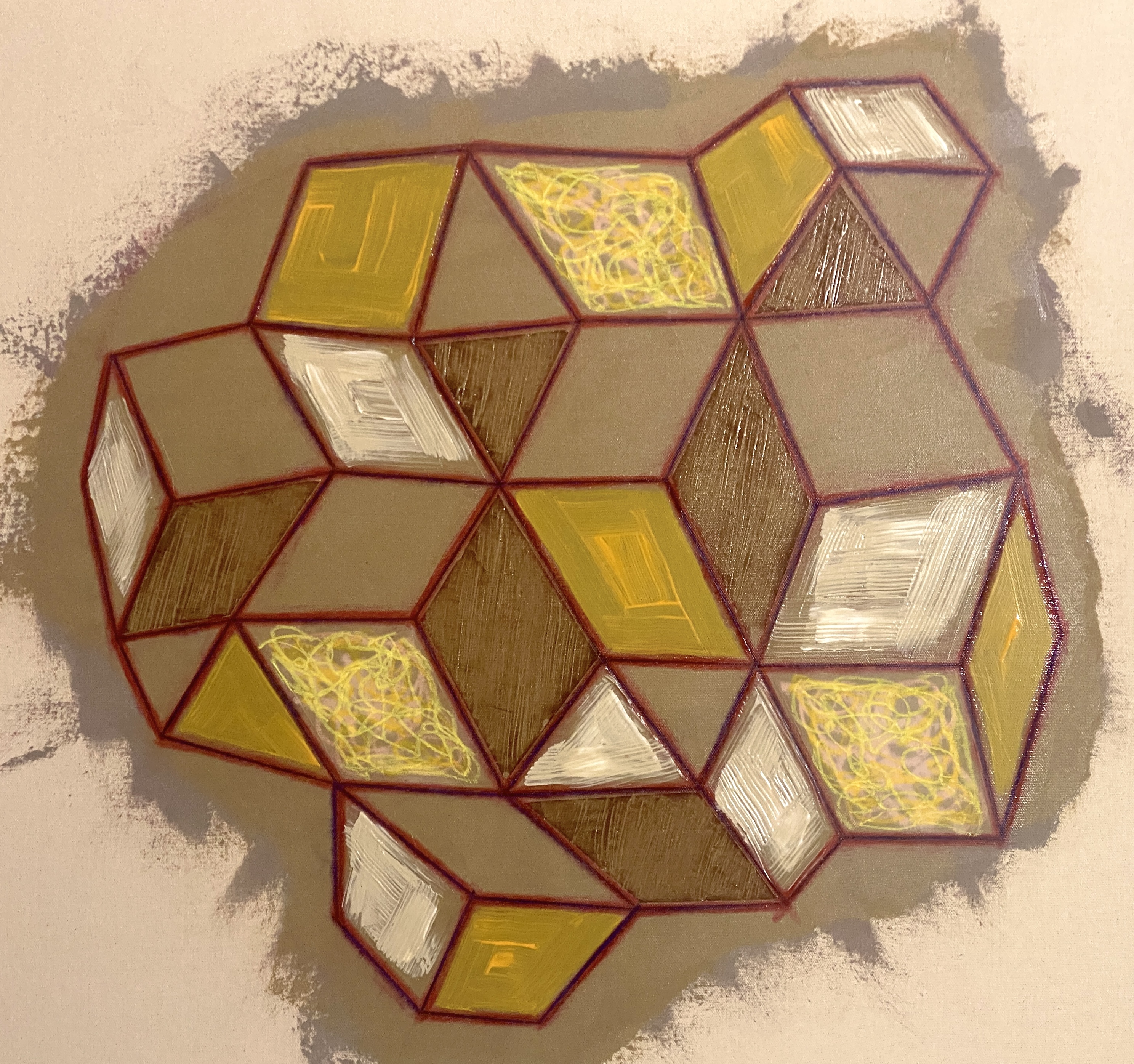

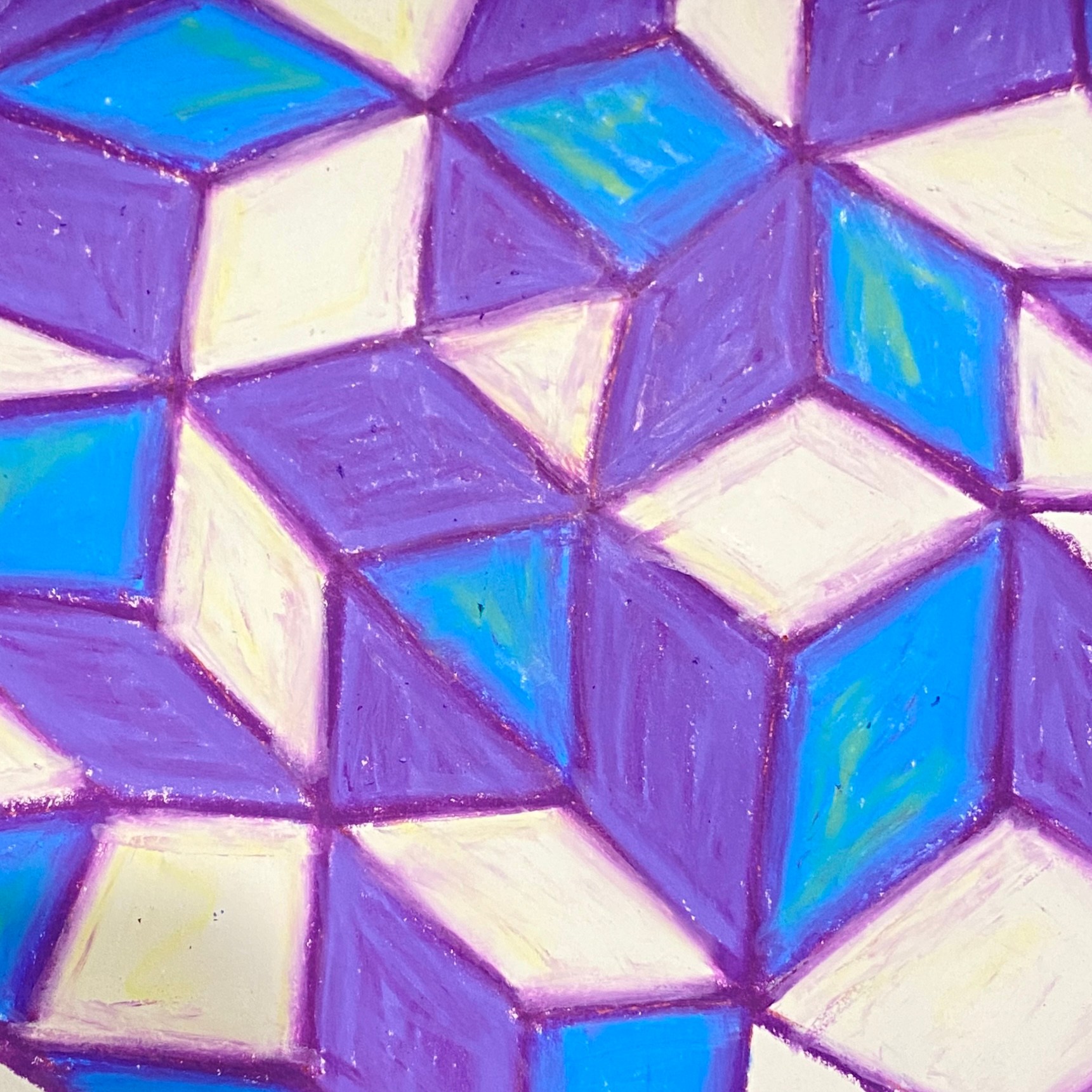

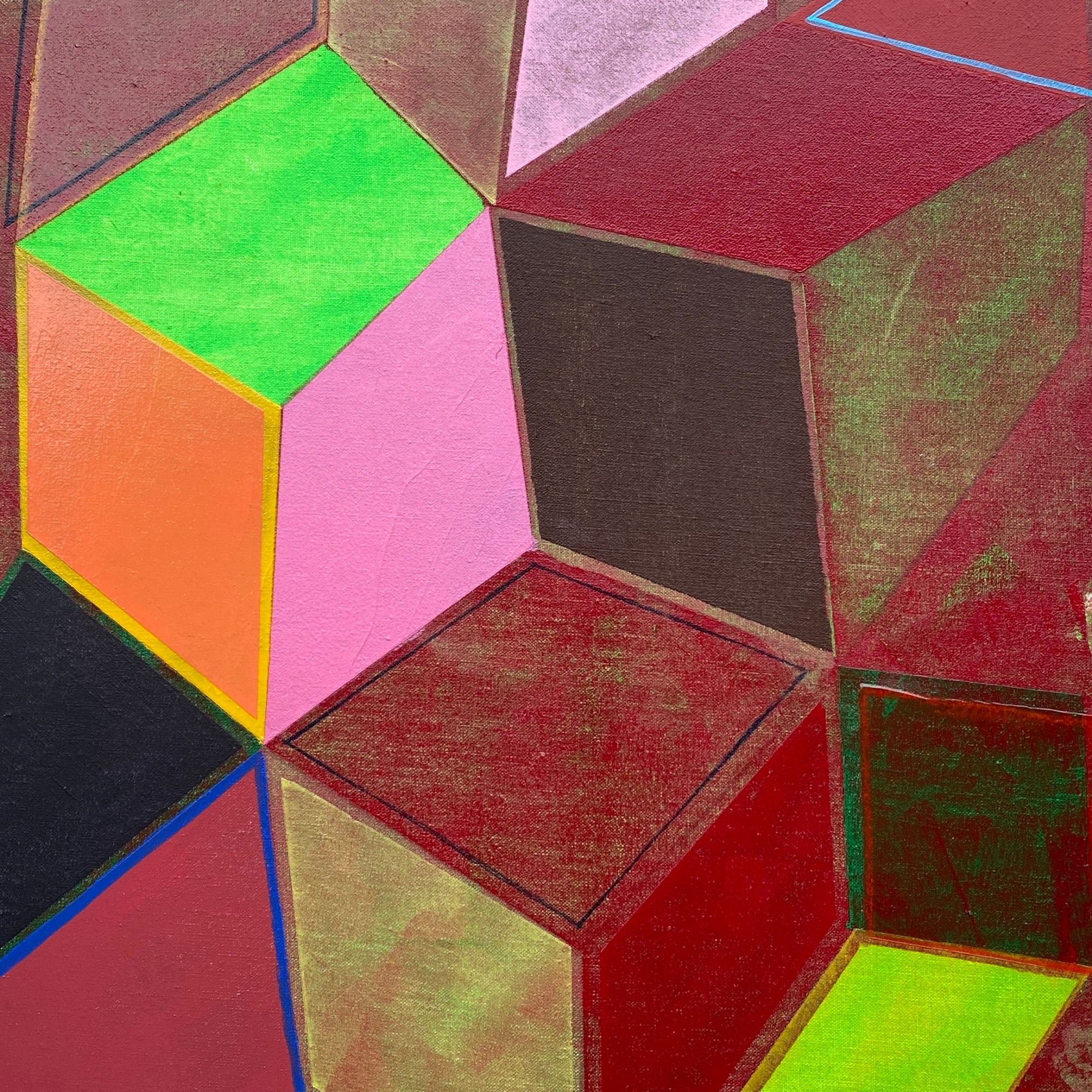

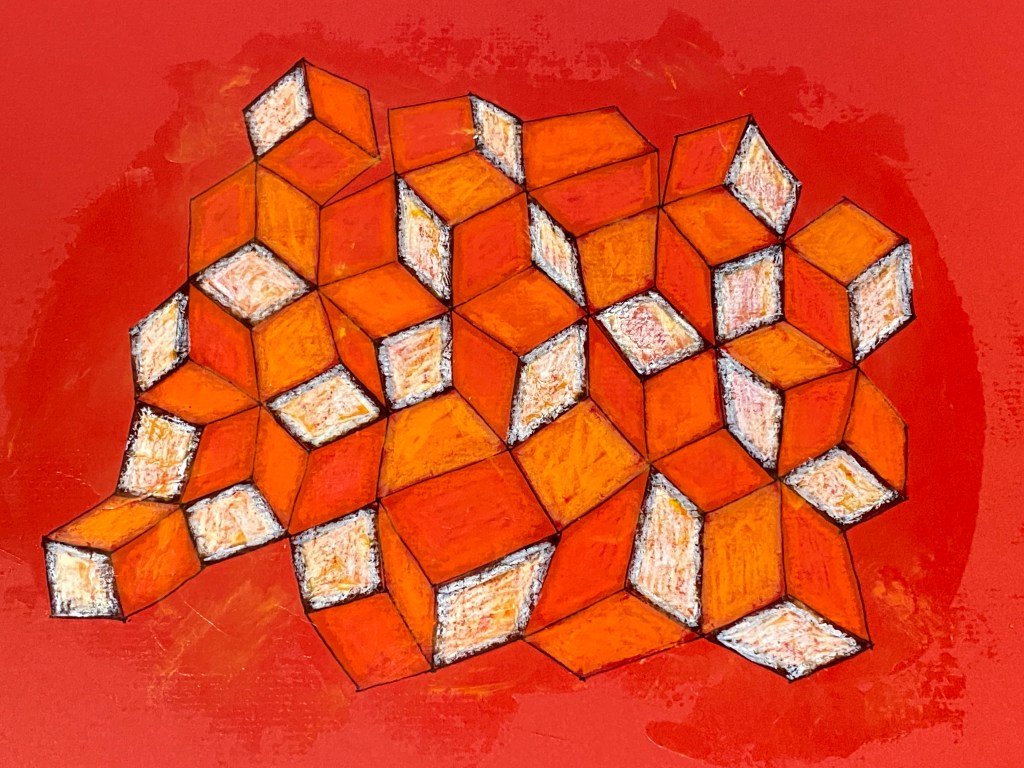

So to cut to the chase, I didn’t come back from sabbatical with a major change in the direction of my practice. The cube persists. It feels gratifying on one hand to know that I can still find value in mining it and the fact that I am open to change I hope is a good sign that it is a vehicle for developing themes and not an end in itself.

There are some wins that I’ve had this year that this break has given me the time to reflect on, including shaping some goals for future growth of my practice. At the risk of sounding, like I am flip, or even worse, just a hobbyist, my practice hasn’t included a lot of goal setting, and by that I mean intentionality around what I want it to look like at some future time. I have had specific targets, like getting back into teaching, or curating, and the next stage I think involves stacking and staging several, including some that get broken into pieces. And fundamentally, the amount of progress I’ve made in the quality of painting has motivated me to push even harder. I made some pretty good paintings which makes me want to try for great paintings.

I also learned about myself- that I can be alone and be OK with that, that there are strategies for organizing work flow that would unlock the level of productivity necessary to satisfy commercial demand, and that I really struggle to read nonfiction (a good idea can easily catch my attention and turn my thoughts away from the text that follows).

That’s it. Which is also a win- it would have been pretty deflating to find I was so unhappy with my life once I got a break from it that I needed everything to change..

Titles

One of the projects I am looking forward to is an upcoming Instagram Live session with Charlotte from Charlotte Russell Contemporary. Which lead to me needing to update my inventory.

Titles are usually really easy for me. (from my artist statement) I don’t usually title pieces before they are shown so the audience will engage first in looking without anchoring to or filtering a concept. Said differently, I think anchoring a viewer with an phrase (titles usually imply a subject) tethers them to thought and language and distracts from contemplation.

During a recent art excursion with my main homeboy About Half, I got to see a fannnn-tastic Stanley Brouwn exhibit at the Art Institute. The titles of so many of the pieces were just perfect. It left me deep in… contemplation! Upon my return I resolved to think more about how I could use titles to point the viewer towards the idea of contemplating (the) painting.

One solution that came to mind was to point the viewer toward contemplation by creating titles from the perspective of a Modernist/formalist. I want the work to refer to itself. A title is a way to point to an idea. So, point to the idea of a painting that points at itself.

Now obviously, I can’t go back in time and ask one of many such practitioners. Enter Chat GPT.

I’m not going to use this article to write about the implications of AI evolution, that’s another, upcoming one. I’ll just note for now that, as an artist, you have to acknowledge this stuff and shape some of your thinking around it. For purposes of this article, I’ll also note that I see this moment’s iteration of AI as an amalgamation of all humans have thought and written. And specifically, that includes a lot about abstract painting, by lots of writers from said era. Why not ask the AI to simulate one (and spit me back a title that would, if read by a viewer, point to the type of language forms that were used to first encapsulate the idea of a painting that points at itself)?

I see this method of titling as a collaboration, and as a way to create a reflection of us back to ourselves (IE, the work points at the viewer as part of the subject).

Following are several images of pieces that our future overlord helped me name.

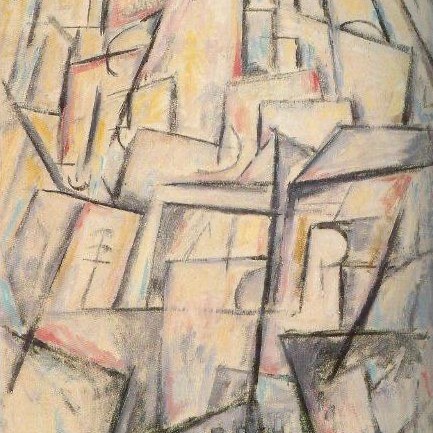

User: Please suggest a title for a painting. It is on canvas, stretched over a small polygon (less than 20” on any side). The predominant colors are pink, red, blue and white. The composition is made of interconnected solids rendered in isometric perspective which sometimes conflicts with itself. There appears to be a light source which does not resolve the subject entirely as a place or space. It would be described as abstract. It is very similar to many paintings made in the first half of the twentieth century.

ChatGPT: “Interplay of Chromatic Fragments”

User: Would an artist from that era name it differently and if so what would they name it?

ChatGPT: If we consider the naming conventions of artists from the first half of the twentieth century, particularly those associated with abstract art movements such as Cubism or Constructivism, they often chose titles that were more conceptual or evocative rather than descriptive. Here are a few suggestions for a title that an artist from that era might have chosen:

- “Ethereal Geometry”

- “Synthetic Symphony”

- “Confluence of Colors”

- “Spatial Rhapsody”

- “Transcendent Abstractions”

- “Harmonies in Contradiction”

- “Luminous Intersections”

- “Contours of the Sublime”

- “Dialectic of Form and Space”

- “Transcending Perspectives”

These titles capture the spirit of abstract art during that time and convey a sense of ambiguity, exploration, and experimentation in both form and color.

—

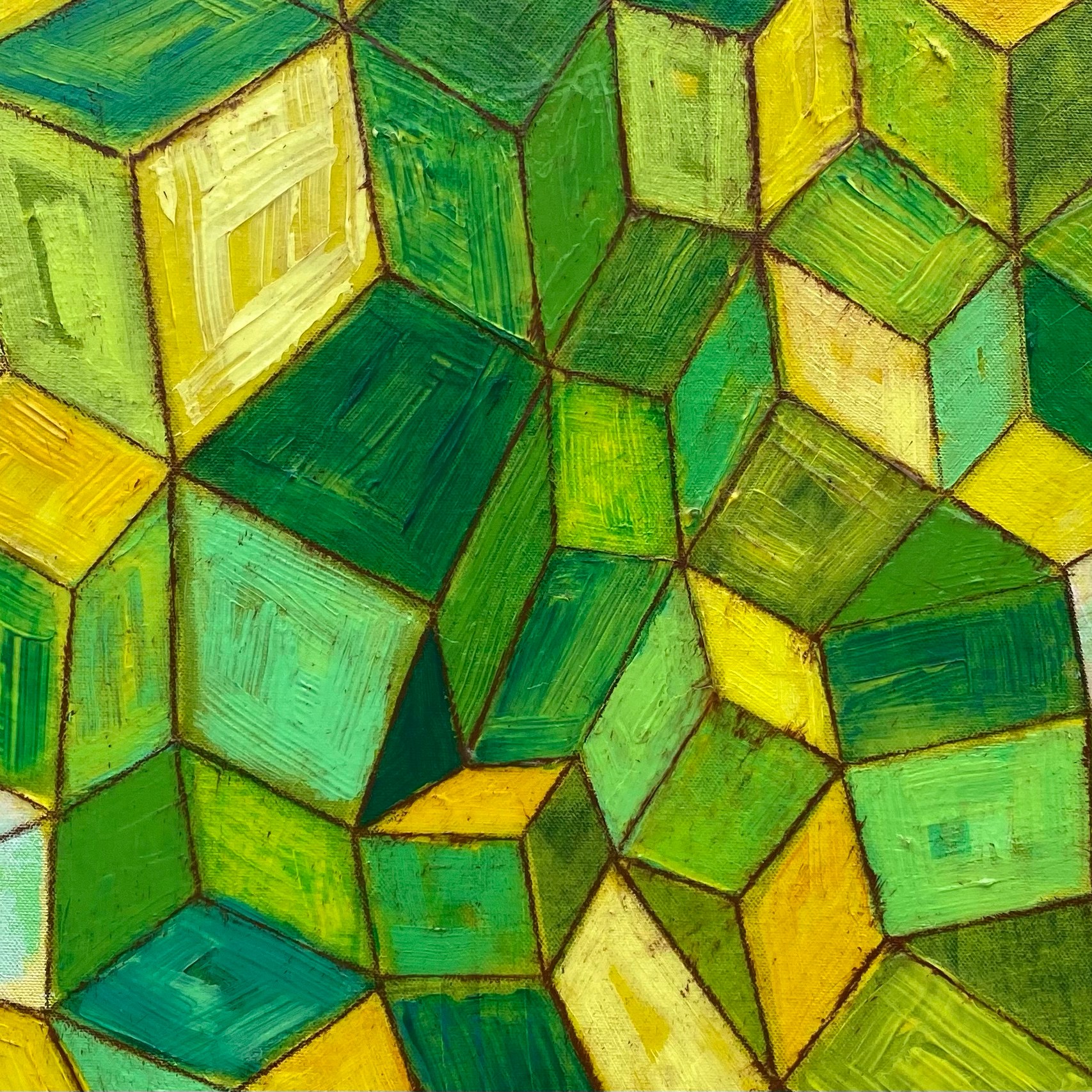

User: Please suggest a title for a small painting. It was made in the year 2023. It utilizes connected trapezoids, some of which imply isometric cubes. The paint application is textured, making use of a pallet knife. There are also drawn lines demarcating the edges of the trapezoids. Heavy use of yellow in combination with blue and green makes certain parts of the composition appear to glow. Although a contemporary composition, please suggest a title from the perspective of an artist that would refer to themselves as a formalist artist from the 1960s.

ChatGPT: “Chromatic Constructions: Luminescent Geometry”

User: “Thank you. What do you think a contemporary artist living today would title such a painting?”

ChatGPT: “Transcendent Geometry: Luminous Horizons”

—-

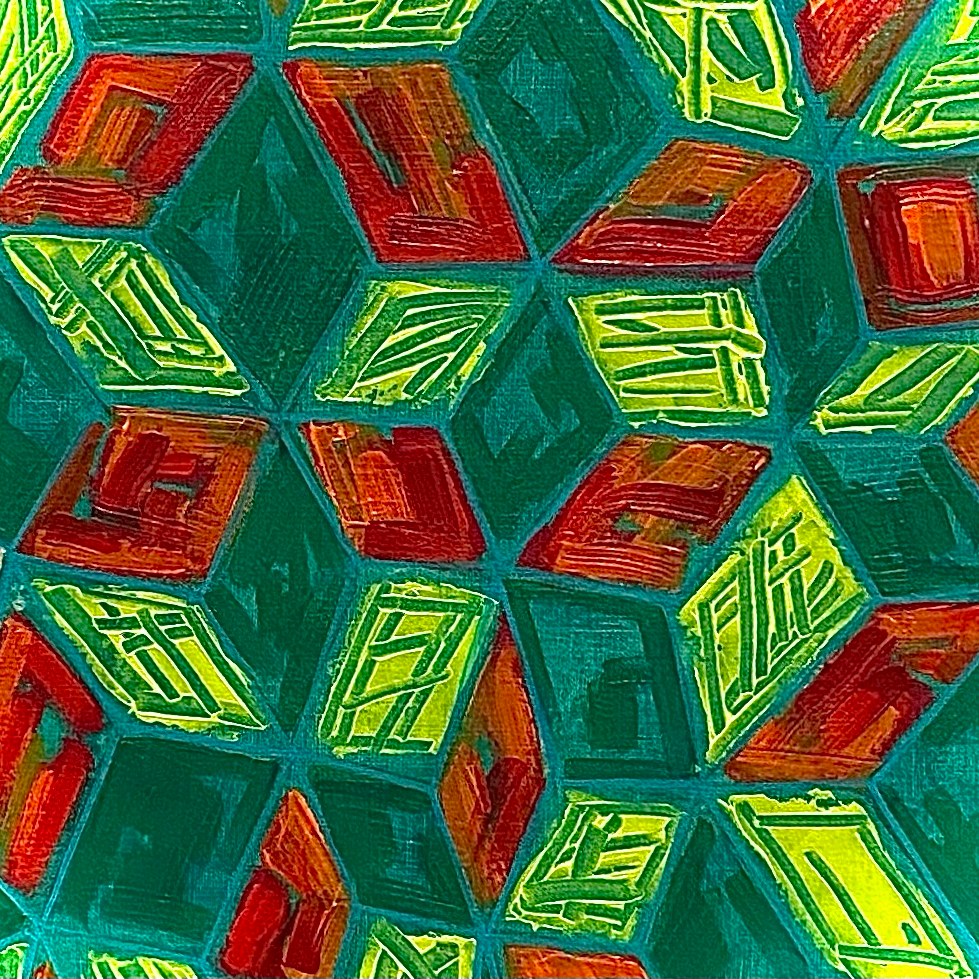

User: “Please help me name a small, abstract painting. The composition is an amalgam of trapezoid shapes, some of which reference isometric cubes. The painting is mostly thinly applied and some of it is transparent. There are hand-drawn and taped lines and edges. The support material is muslin and it can be seen in its raw form in many places. The color pallet is very 1980s, while the composition looks like it dates to the late 60s. The artist is a white, American man who intends the work to be perceived as less than inviting and not quite garish either. There is an almost romantic commitment to idealism, but it is not showy or pretentious.”

ChatGPT: “Based on the description you provided, here are a few name suggestions for your small, abstract painting:

- “Fragmented Reflections”

- “Translucent Geometry”

- “Trapezoidal Echoes”

- “Luminous Subtleties”

- “Muslin Memories”

- “Cubist Whispers”

- “The Unassuming Ideal”

- “Chromatic Nostalgia”

- “Ephemeral Structures”

- “Modest Ambiguity”

Feel free to choose or modify any of these names to best suit your artistic vision.

—

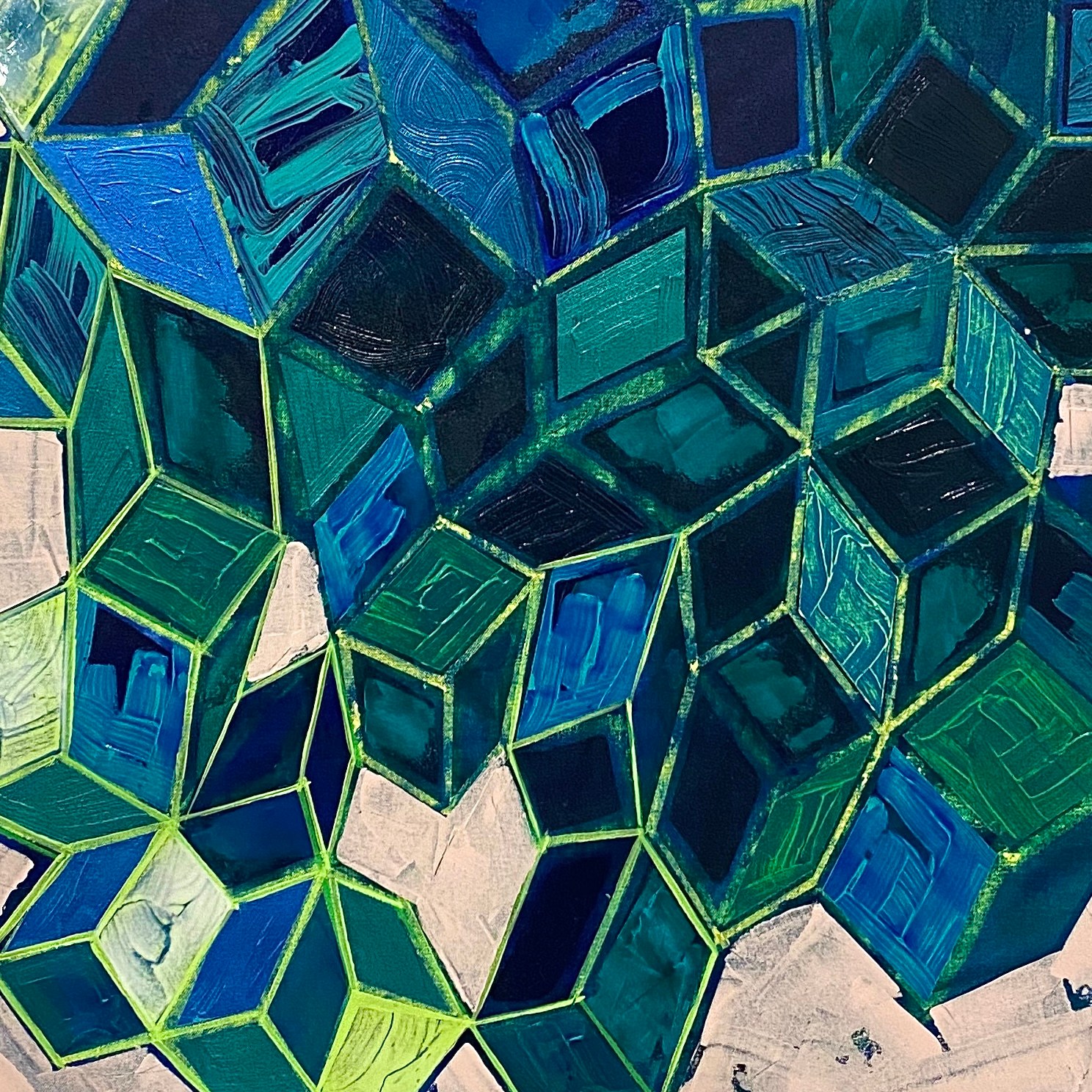

User: “I would like at least one suggestion for a title for a small painting on a shaped canvas (less than 2 feet in any dimension). Raw canvas is visible around some of the edges of the painting, and white primer is also visible- the application of paint builds up towards the middle of the canvas. Much of the paint is transparent acrylic. There appear to be cubes but there is not a consistent light source. Some surfaces appear rendered and others appear to be sections of larger images. It would be called geometric abstraction. It was made by hand and is the result of a number of studies. The only interaction with the digital has been this request to help suggest a title.”

ChatGPT: “Title suggestion: “Fragmented Prism”

User: “What happens to a prism if it is fragmented?”

ChatGPT: “If a prism is fragmented, it means that it has been broken or divided into multiple pieces. In terms of its optical properties, a fragmented prism would no longer function as a cohesive unit to refract and disperse light in a controlled manner. The fragmented pieces may scatter or distort light in unpredictable ways, resulting in a disrupted and fragmented pattern of light and color. Metaphorically, a fragmented prism could represent a shattered or disrupted perspective, where clarity and coherence are lost, and the elements are scattered in a disordered fashion.”

—

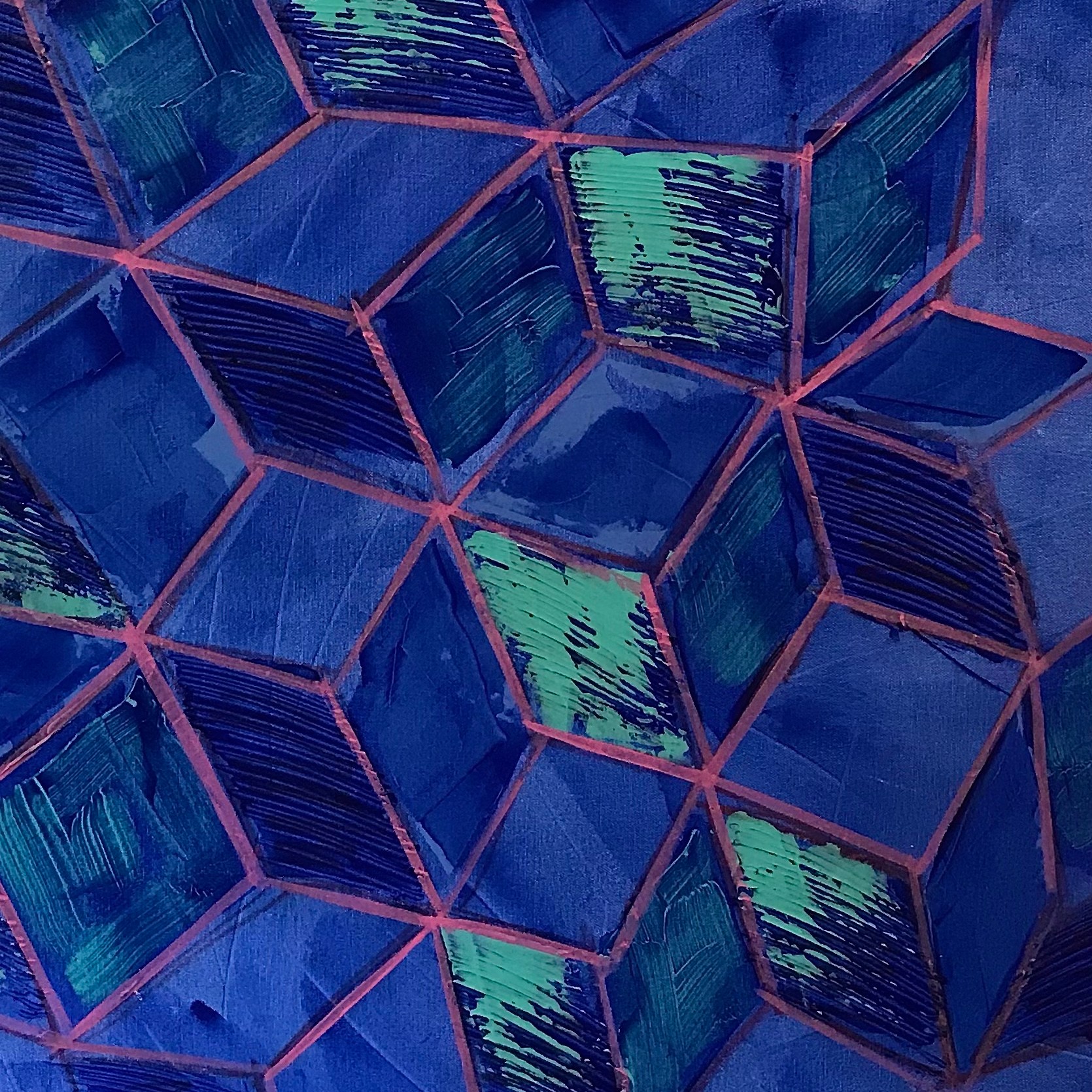

User: “Please provide at least one example title for an abstract painting that I recently made. It utilizes acrylic paint, and many of the types of additives for acrylic that impact its sheen- some areas are iridescent, others are dead flat compared to higher, glossy surfaces. It is a medium size canvas in a trapezoidal shape, and the raw, blue canvas is visible around the edges. The lines between the compositional elements- which are trapezoids that occasionally form and imply isometric cube-like shapes- are crisp (you can see in many places they were made using tape). It is definitely an abstract composition. Please keep in mind the history of geometric abstraction and the point in time in which the painting was made. There is no intended “subject” for the painting; I intend for it to exist in a place where it is considered without reference to an idea other than it’s need to be contemplated in order to have purpose.”

Chat GPT: “Title: “Luminescent Intersections: A Geometric Ode to Contemplation.” Explanation: This title captures the essence of your abstract painting while referencing the history of geometric abstraction. “Luminescent Intersections” refers to the play of light and sheen created by the acrylic additives, highlighting the iridescent and flat areas. The use of trapezoids and implied cube-like shapes in the composition is emphasized by the mention of geometric intersections. The title also alludes to the contemplative nature of the artwork, as you intended it to be considered without a specific subject. Finally, the inclusion of “ode” in the title adds a poetic touch, elevating the significance of the painting and suggesting a deeper appreciation for its purpose.”

User: “I’ve already used the adjective luminescent in a recent title. I’m inclined to call it Geometric Ode to Contemplation unless there is a different adjective that would accomplish the same thing.”

Chat GPT: “Certainly! If you would like to avoid repeating the adjective “luminescent,” here’s an alternative title for your abstract painting: “Ethereal Intersections: A Geometric Ode to Contemplation.” Explanation: The word “ethereal” conveys a sense of delicate beauty and otherworldliness, capturing the effect of the various acrylic additives and their impact on the painting’s sheen. The term “intersections” still references the geometric elements in the composition, emphasizing their crispness and the use of trapezoids and cube-like shapes. The phrase “Geometric Ode to Contemplation” remains intact, signifying the intended purpose of the artwork—to be contemplated and experienced without a specific subject or idea.”

Sabbatical update 7-17

Still having a really productive trip, on a lot of levels. I’m getting better at giving myself permission to enjoy all there is to do here- given this opportunity I think most people would make an effort to have some fun. And happiness can be an art supply, folks!

At first I felt some amount of guilt because I wasn’t painting all day- this is supposed to be a residency right (in my head, every artist whose residency I’ve “seen” on social media has just cranked it out)? It’s amazing what kind of pressure we can put on ourselves, even when I am in the studio working at least twice a day (and thinking and processing more often than that). Fourteen plus sessions per week is a 5x increase over the ~three sessions a week I can cram in back at home.

One of the topics that has interested me for some time is strategies to apply paint which allow viewers to see through layers- I don’t intend for the creation of the work to be completely transparent pun intended, quite the opposite. It also, frankly, allows acrylic paint to be something oil can’t- thick and transparent. Love the idea of a physical thing having an ambiguous optical presence.

Also had a happy accident with a product I got from Utrecht that turned out not to be gloss gel. It gives me a 3rd sheen option in addition to the complete, dead flat of matte gel and high gloss gel.

Have been looking to Max Ernst for inspiration as well, and plan to explore (as he did) the use of grattage (which I have used in the past) and decalcomania (which I have not), both of which it’s safe to say were mastered by Ernst.

Speaking of looking at artists that do landscape, what is up with all the green that’s showing up in my studio oh wait…

Color…

What a topic. Especially for an abstractionist who works exclusively with color, line, form and surface. It’s been on my mind since I read this Jason Stopa interview recently where he talks briefly about intentionality in color choice. He says “I think a lot about color “families.” My color isn’t arbitrary; it’s color that’s rooted in early Henri Matisse, Bob Thompson, Stanley Whitney, Mary Heilmann. It’s graphic, optimistic color loaded with content about mythologies, Arcadia, and joy.“

I wrote the phrase “relationship to color” down the first day I arrived at my sabbatical destination.

As far as my process goes, “in the flow” I make decisions based on prior decisions (mark, react; repeat). If I’m being honest, lately I’ve been starting paintings loosely from a series of drawings I did, and I tend when drawing to work with what’s at hand, which means I’ve both selected and limited my pallet and, to the point of this inquiry, not intentionally. I could argue that’s because my choices are more about creating contrast or at least distinction to foreground contradiction. Still… is there an unconscious/subconscious theme to my color choices though?

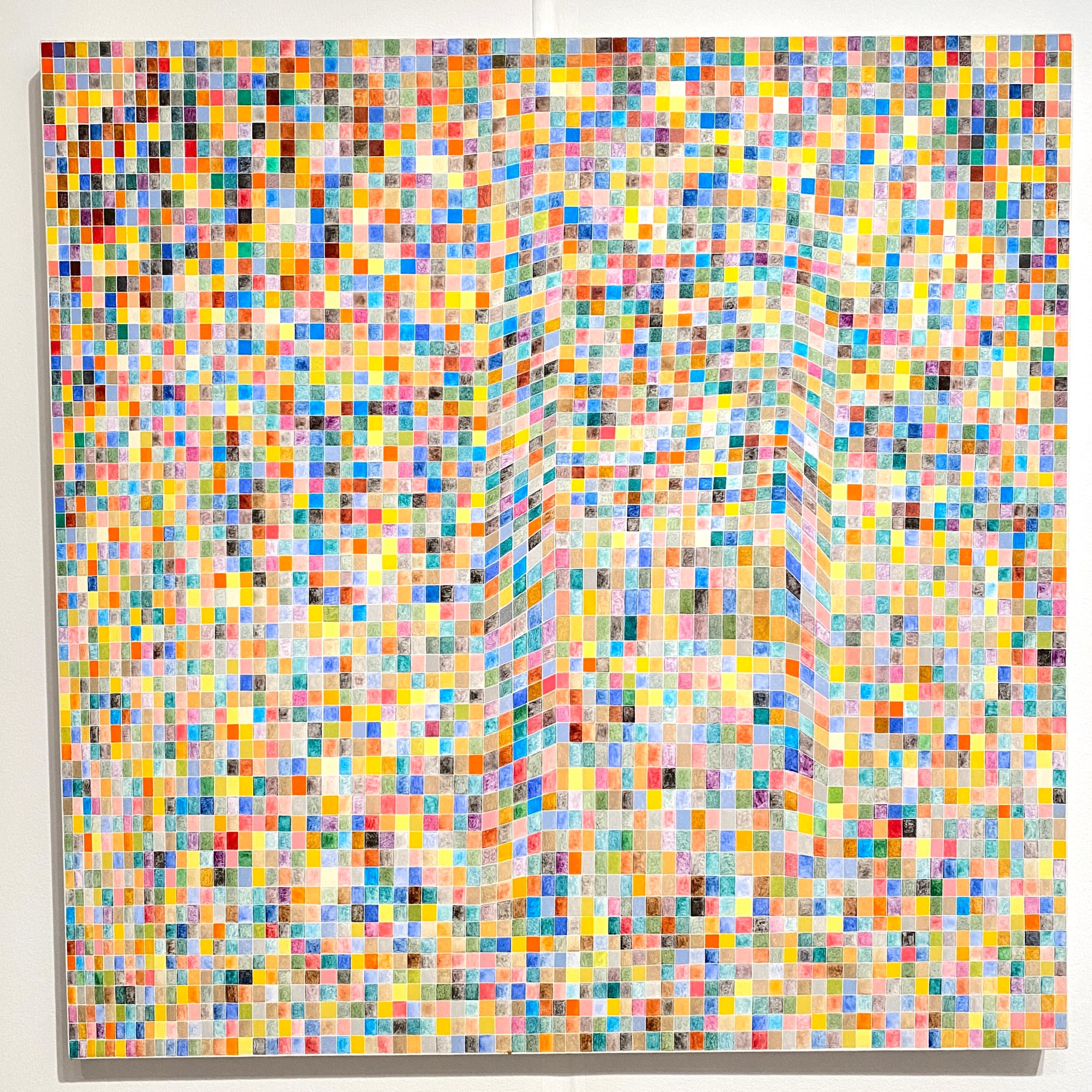

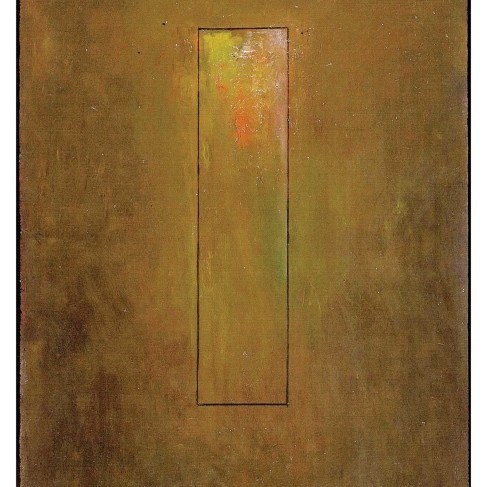

I decided to use technology to put a number of images all in one place for comparison- below are cropped photos of my last 23 paintings plus one drawing with crayon that’s basically a painting. Since I often write and talk about my interest in and the references my use of the cube makes to Modernism, I think it’s fair to assume that I find or make compositional choices in general that harken to early to mid-twentieth century painting by Europeans and Americans. So, do my colors look like Modernist colors? The second gallery below are the last 30 artists I blogged about that made the work pictured some time between 1915 and 1960, with most of them dating from the ’40s and ’50s (and “yes” I’m aware of the dual truth that these artists are the Modernist painters to which I am personally attracted, which is not comprehensive, nor do I intend to be).

…and here’s the Modernist work.

A few things pop out- a lot more blue in my work, a lot less browns and definitely less white (my hues are more saturated in most cases). I’ve worked with bold colors before, intentionally choosing high key ones that reference ’80s video games and cartoons. At the time I would have said bourgeois escapism, generally, was a theme, which doesn’t land in 2023 like it did in 2000- in particular in light of this recent Jonathan Stevenson article over at Two Coats, which isn’t critical of nostalgia so much as noting that when it’s romanticism full stop it’s “dumb.” My view of and interest in Modernism is definitively not romantic. I am interested in relevant ideas, like the parallels with today to another, earlier time when change became clearly necessary, and in how the notion that the artist did not owe anything to history became prevalent. Though I wouldn’t call myself or my practice activism, I am also, when possible, engaged in using the teaching of this period as a way to address and decolonize the more problematic aspects of many of the creatives and thinkers we traditionally center in this epoch.

I’m not sure where I’m landing to be honest- I generally try to avoid making abstract paintings that are representations of ideas (including ideas about cultural origins of certain colors) because of my concern that the work then becomes nothing more than a codex. And I’m not worried any way- I know mechanically that I’m competent to create any color I chose (I teach color) and I’m quite certain I don’t work my work to ever “just” be an exercise in flexing on some color theory. More recently I’ve begun to look for more “oooh/aaah” in my painting (please go see my newest, “left” and “Fragmented Prism”, in Open Source at Lump), so there’s nothing likely to change about my gravitation towards high levels of saturation.

Sabbatical update 7-4

Happy to report that my time in Marshall has been really great. Like, really great- this is a really cool little town full of interesting people. And I have been making art, which was the reason to make this sojourn. Two weeks in, I have several finished pieces, including a mixed media piece on board that’s very red. I have more underway, including one redo for the top left piece, which taught me a lot about texture/surface and sheen that I plan to apply (or as it were, reapply). Keeping scale small to mid-size for the moment.

Also found a good bit to do to get ready for OpenSource which I guess is not surprising given that it’s actually 2 shows with 30 artworks. One of the things I’ve done to promote the show is a series of reels about each of the artists- head on over and check out Durham Art Guild’s IG feed to see them (or mine).

Personally, I have been working on taking the time to slow down and cook from scratch, and getting out and enjoying the area as well- I’ve even started taking yoga in person, something I haven’t done since pre-pandemic. The weather has been pretty rainy but that’s been just fine since the “studio” is here at the apartment. There’s a good bit of time that goes into just living, especially when you drop it down into a lower gear (I typically run all cylinders). I’ve made myself sit and read* a few times, especially as I’ve noticed the low-level, anxious… hum that animates me most days (“dooooo something!”) and often results in me thinking about something I “need” to do, other than what I’m actually effn’ doin’ in the present moment. *Amy Whitaker, in Art Thinking, spends some words on the idea that “the way to navigate is not toward a solution but from a question .”

Will this time change me?

Probably .

More curating!

I hope that most of you reading this are from the Triangle and will be able to come out and see my “next” foray into curating, an exhibit I’ve titled Open Source**. I write “next” because technically I developed and began shopping around the proposal for this exhibit (checks email archives…) in early 2022, before I even thought up or proposed ExtraSpectral, which ended up being my initial foray, at least on the execution side. The show is currently programmed for two venues in 2023 and another in 2024; the group will use the latter show to further develop ideas around our relationship to each other, abstraction as a modality and the idea of “source” (being shown at a post-secondary institution will also hopefully give us a chance to interact with art students).

Show Statement

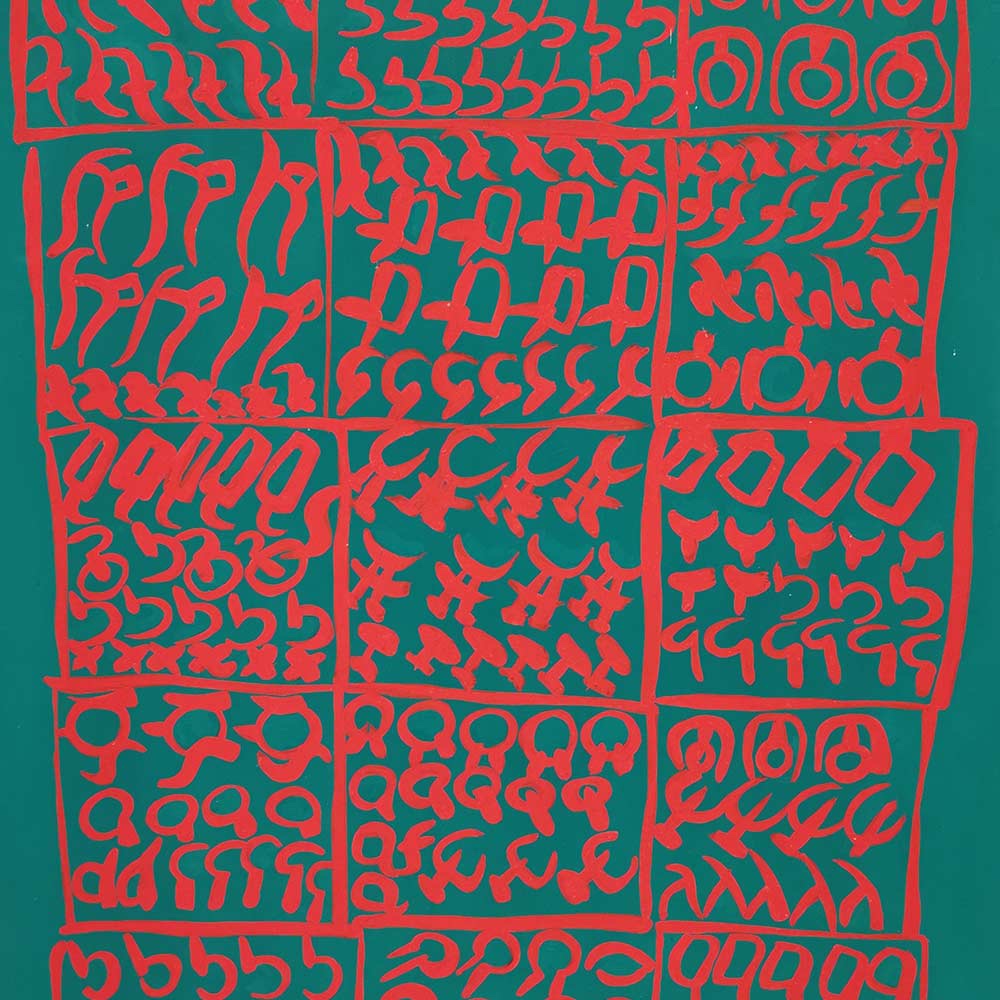

In the world of software code (the hidden structure of much of the world as we view it) Open Source is source material that is made freely available for possible modification and redistribution. Open source is a decentralized software development model that encourages users to take a set of tools and custom-fit them for a new purpose. At our current point in the history of making Art, there is also a decentralized framework within which abstract artwork can be and is made. No single artist or group owns the source of meaning for this modality, and a wide range of collaborations with and utilizations of the elements developed out of the historical canon is possible, as well as incorporation of content and materials from outside that world. In the space needed for and occupied by abstraction, an openness is required, for creator and audience. The artist must be open to the ways in which the source materials of the work, including subjective content, inform decisions about everything from composition to titles. And the audience must be open as well since abstraction’s signifiers (color, shape, surface) are non-literal. Perhaps most importantly though, the title of this show brings our awareness and acknowledgement to- celebrates- the variety of source material possible in our time of art making. Artists (in alphabetical order and repeated below) Freddie Bell, Sterling Bowen, Natalia Torres del Valle, Jason Lord, Peter Marin, Jean Gray Mohs, Cindy Morefield and Carson Whitmore all approach non-figurative artwork from different vantages, personal and conceptual.

- Lump Project Space (Raleigh)- July 2023

- Sertoma Art Center– Jul/Aug 2023

- Wilma W Daniels Gallery, Cape Fear Community College- Fall 2024

I owe special thanks to so many people- especially the artists in both shows!- who have taken this ride with me and provided support. I’ve said it before and it bears repeating, the arts community in the Triangle is really special. I love you guys!

**BTW, did you know the phrase Open Source was coined by Christine Peterson?

Sabbatical

My “day” job, about which I am very passionate, is in the field of clean energy. My career in this space is the result of an intentional decision over 2 decades ago at a time when I abandoned my goal of securing a Master of Fine Arts in Visual Arts so that I could become a college professor. It wasn’t the first time I changed career tracks- in undergraduate school I switched from Architecture to Fine Arts/Humanities after my freshman year. While I didn’t leave graduate school to specifically enter another field, I knew I’d want to have a profession and that I’d need to be able to feel invested in my work to be satisfied. That’s why, more than two decades later, I find myself at one of three different B corps for which I’ve worked, and about to take advantage of a pretty amazing benefit- a paid, eight-week sabbatical. I recognize the immense privilege of this moment and plan to take full advantage of the opportunity.

How? Well, for some time now (since 2019-ish), I’ve had 2 careers. I began making Art again in late 2016. I basically had a midlife crisis, a phrase I don’t hear much anymore and which we used to joke in grad school was not part of an artist’s fate (since we spend so much time in self reflection already, why would we ever be in crisis?). Mid summer, as we were still reeling from a traumatic freshman year for our oldest who had severe depression coupled with regular episodes of severe hallucination, I unexpectedly lost my job on the same day we had begun major home renovation which had meant almost emptying out our savings account. That evening, as I was trying to be a normal parent at our kids’ swim team’s meet, I fixated on some really amazing cloud formations- that June had been rife with almost daily thunderstorms and some of the late-day visuals were other-worldly. I took what was the first photo of a project that took almost 2 years, resulted in my first Instagram feed, and, eventually, in becoming a practicing artist. All because I stopped in the moment and paid attention to what I was seeing and appreciated its visual qualities.

Towards the end of the project, which I promoted on Instagram as #abstractionallaroundus (I saw the photos as automatic compositions- line, shape, color, texture), I began to explore more tactile modalities. I had always considered myself an abstractionist and despite practicing what was basically landscape photography, found the return to non-figurative mark making natural and invigorating. Within what felt like no time at all, I was making work on paper and canvas weekly, entering calls for artists and showing work. In short order I also began blogging, teaching, and curating, which necessitated integrating my practice into not only my life (and around the perimeter of a what was technically a full time job) but also within the local arts community.

These two “lives” are adequately resourced and non-conflicting, a dry way to describe the division of my energy, and also not an exaggeration. My Art-world friends know I’m not what our ecosystem denotes as a “full-time practitioner” and they accept my “joke” that Sterling Bowen, Head of Origination for American Efficient, is my “alter ego.”

So why take a sabbatical? What is it going to mean?

A sabbatical is “a rest or break from work; an extended period of time intentionally spent on something that’s not your routine job.” My career as an artist- and I do see it as “a profession for which one trains and which is undertaken as a permanent calling”- is also not my job (a regularly occurring position which has to be done). “Rest” has many benefits- the last 2 years at my job have been, while not physically challenging or time-consuming, emotionally draining at times. A break from such an environment is likely to not only release pressure, it has the potential to reinvigorate passion for my role and the important work that we do.

But that’s not why I applied to take sabbatical, nor will it be the focus or purpose of my time away from my job.

There’s a reason that creatives in the Art World (mostly) strive towards being a full-time practitioner. It’s not (just) the validation that your practice generates enough revenue to pay your studio rent and buy some rice and beans, or that it likely means (requires?) an on-going relationship with a commercial gallery which generates demand for products, which is no doubt also a goal for (probably) most creatives that call themselves Artists with a capital “A.” It would be easy to say we work towards this state “for the love” and that it’s fulfilling to practice as much as we want. There’s also an uncanny relationship between the amount of time one dedicates to a craft and the quality of resulting output. All, also, true- and still, not quite the point.

The object-making part of my practice is all about paying attention to what is happening. Make a mark, pay attention, react. Repeat. Finish a piece, reflect, write about what it meant. With a full-time job and a life, there isn’t room- literally, but also emotionally- to engage in that more than a few hours scattered throughout the week.

What will I see when I can give my practice maximum space? I can’t wait!

Nonobjective

“Nonobjective” when referring to artwork has a particular meaning in the visual Arts. Objective means “expressing or dealing with facts or conditions as perceived without distortion by personal feelings, prejudices, or interpretations.” It seems impossible, to this creative, for an artist to approach such a state- I don’t think I’d be able to make work free of personal feelings, nor would any audience be capable of perceiving without the same. And, while the objects that result from my practice could be called non-objective in the sense that they do not represent or point to objects outside of themselves, I also like the description nonobjective as a way to refer to activities that do not have a destination. Interestingly, the definition in the Merriam Webster link above has very abstract and open terms- an objective can simply be a “goal.” Maybe it is impossible to be either objective or not-objective?

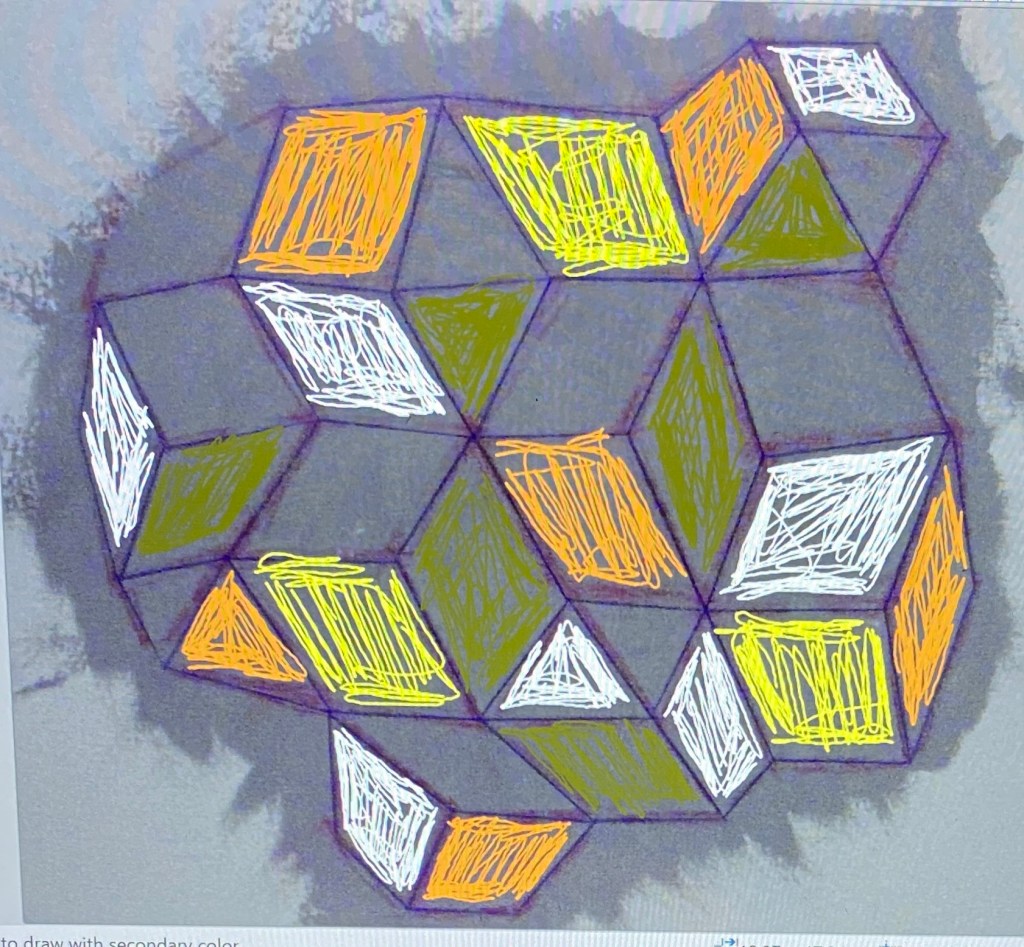

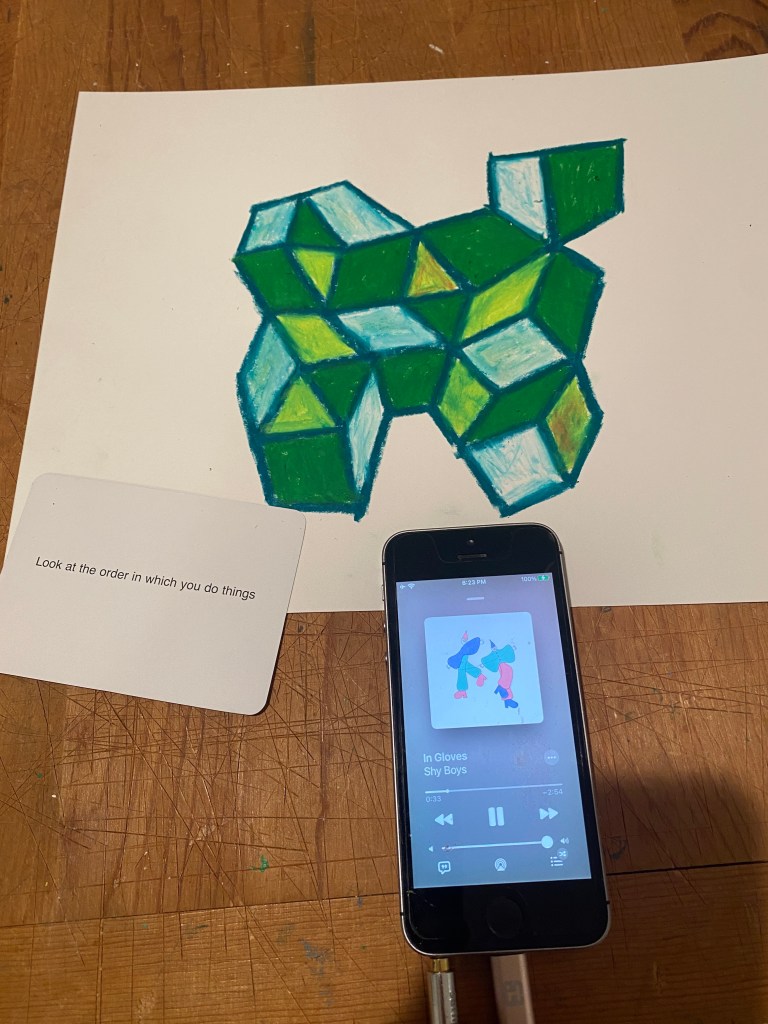

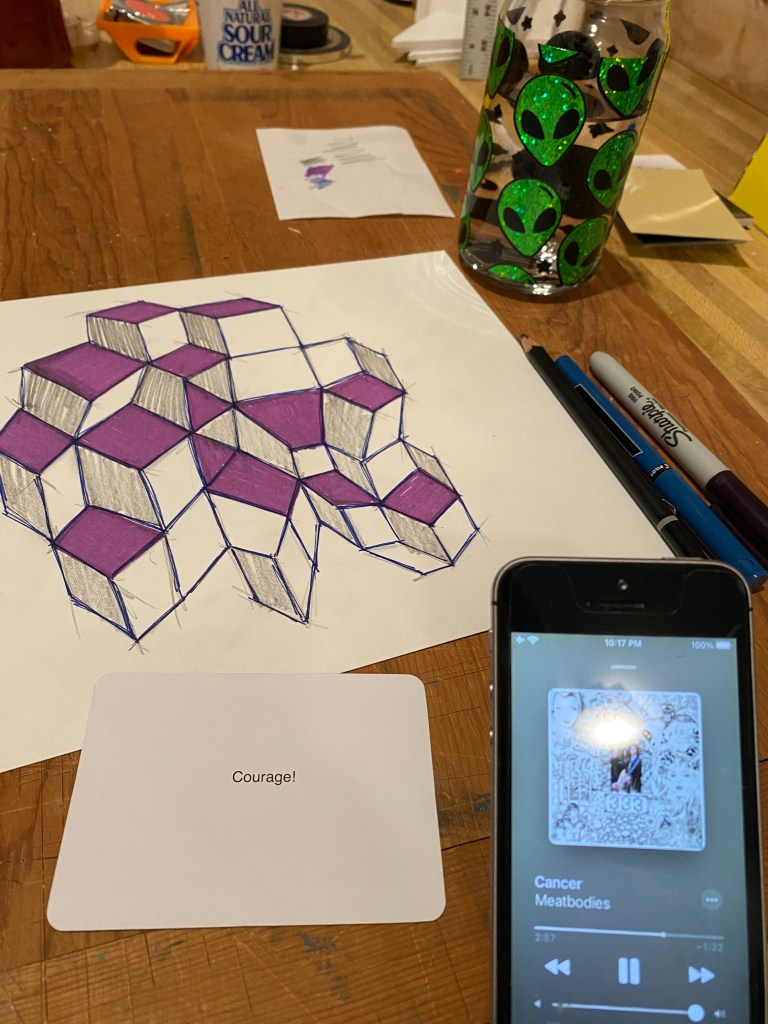

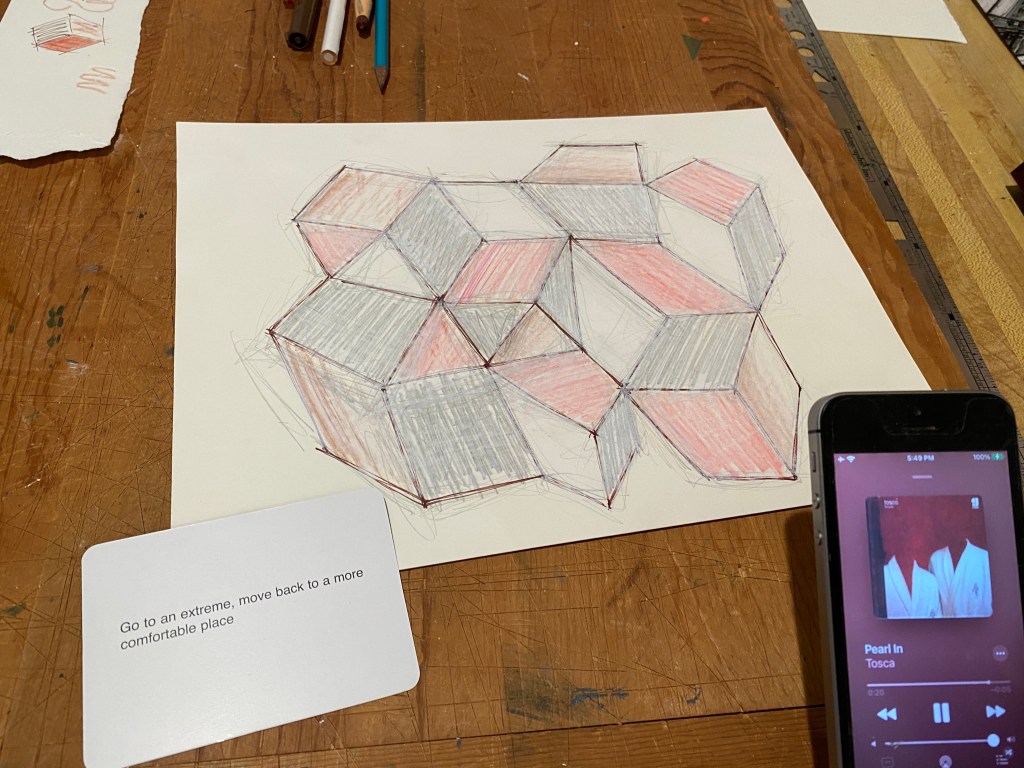

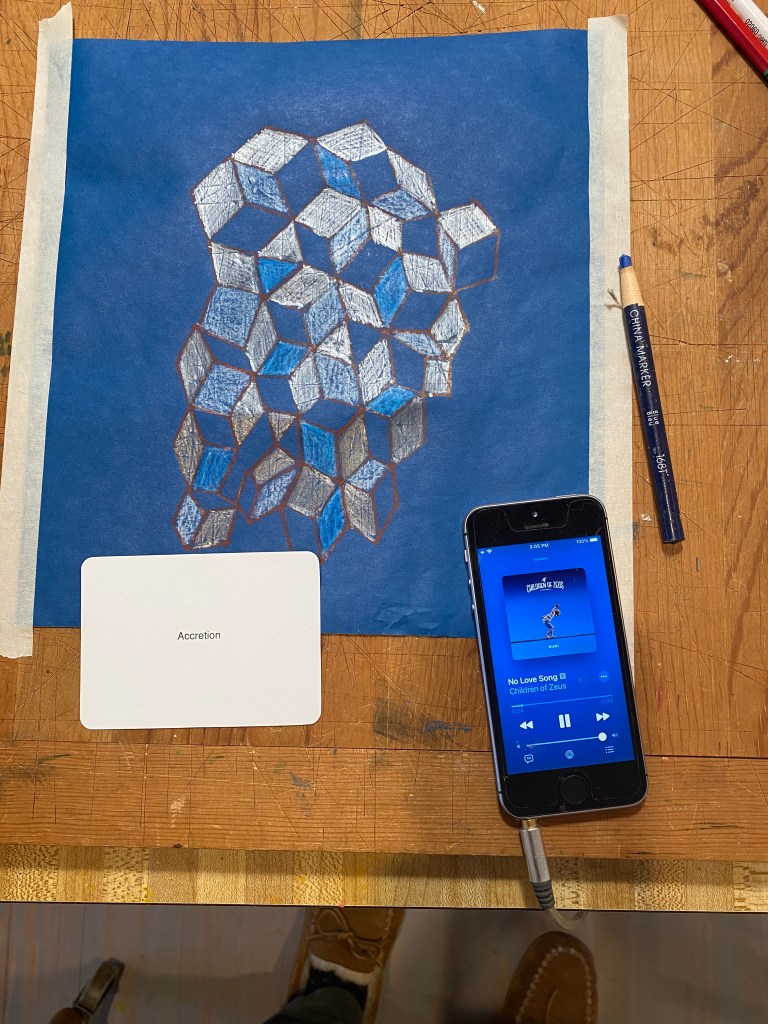

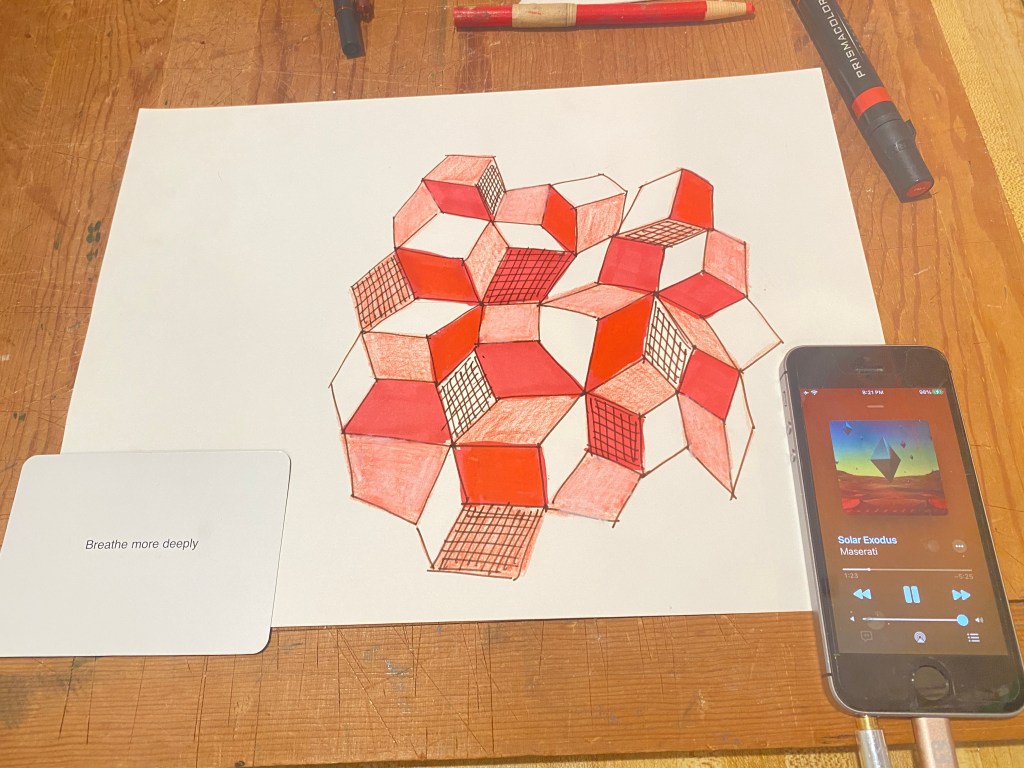

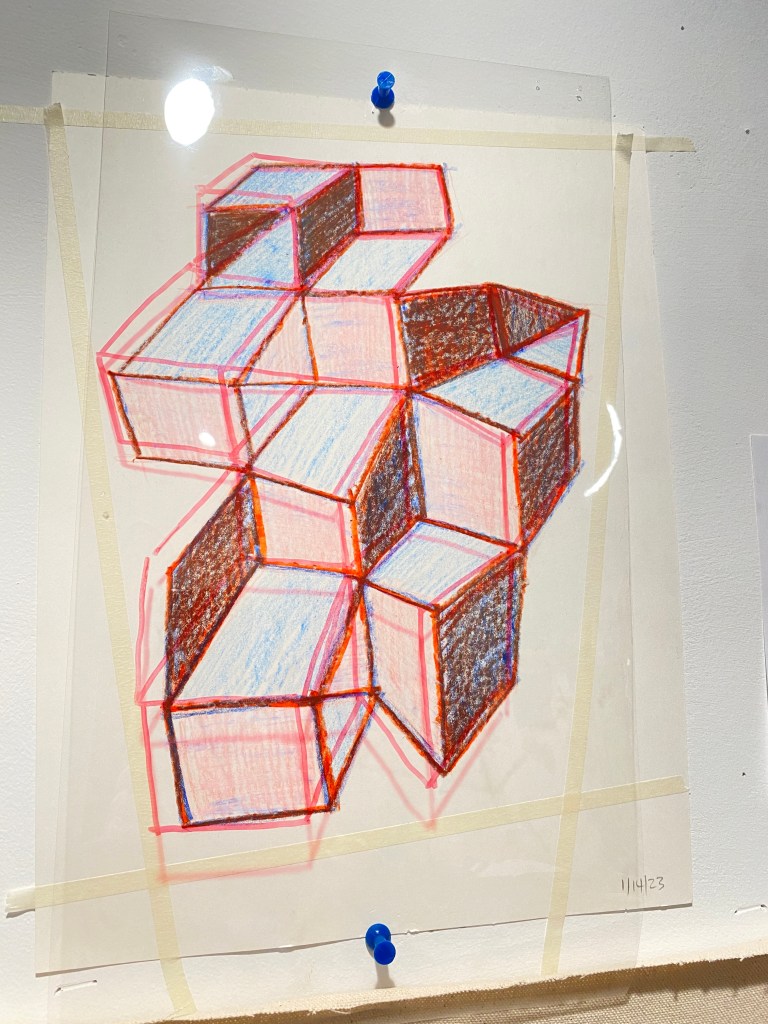

The context for the thought exercise above is the recent resolution of an object. I finished up a piece (first image in the gallery below), which was the last of several iterations of a composition. The object- or perhaps the idea?*- first came to be as part of my work with Oblique Strategies. The first instance resulted from the card I drew on 1/6 which asked “what would your best friend tell you do;” I wrote in my journal that “Michael would tell me to do what feels right” (and what felt “right” was using my cube system to iterate a composition). The result seemed very much… right. Not a thing, not a place, not a surface, not really space; not of this moment or the past. A few days later on 1/14 I drew a card that granted me permission to retrace my steps; seeing the opportunity to revisit something I really wanted to anyway, I responded that “yes, I literally repeated a composition.” I also tried scaling it up on 2/12 because of my attraction to this collection of shapes. At the time I was asked “do we need more holes” (my response was “yes, use color and texture of paper” referring to the absence of media for some trapezoids).

*Sol Lewitt famously said that the idea is a machine that makes the work- work here can be an object. Which is why notions of “object” and “objective” have been on my mind- there is an idea here that is driving the making of the object. BTW the 2 albums featured below are both worth a listen if you haven’t, in particular The Oh Sees joint.

I also used Chat GPT to name this one. There are many reasons to engage AI; for myself I see this “collaboration” as a way to create a reflection of us back to ourselves (if one thinks of this iteration of AI as an amalgamation of all humans have thought and written about abstraction).

A few more images of new things going on in the studio below to round out this update; a couple of drawings that are a revisiting of compositions created during my daily drawing practice (which will impact future paintings), and some images of the largest painting I’ve made in a minute nearing completion.

Formalism

I wrote this essay originally in May of ’23. Below is an update from Oct ’25.

…

Conventionally- academically- the word “formalism” has very specific meaning:

“Formalism describes the critical position that the most important aspect of a work of art is its form – the way it is made and its purely visual aspects – rather than its narrative content or its relationship to the visible world.“

The Tate (source of the quote above) clarifies that this tendency was both a beginning point and a path that lead towards a culmination. As a description of an approach to object-making in the visual arts, “formalism” elicits images of work and words related to the ideas of many artists we classify as Modernist. Most likely, college educated American artists immediately think of the second generation of abstract painters (Frankenthaler, Olitski, Poons) who advanced ideas imported from Europe by their immediate predecessors and often peers, who valued process and intuition. As the story goes, they eschewed gesture and surface and focused on color and shape (form), and were themselves forbearers of artists who followed through on a general reductionist mission for its own sake (Stella, Downing, Kelly et. al.).

The notion that art could not just be but in fact *was* at its highest level of intended function *only* to be understood “on its own terms” is a distinctly Modernist idea that is very humanist and Euro-centric. Its cultural dominance and embedded notions of the supremacy of Western civilization mean it is associated with most of the evils that propelled the last century (pick one- militarism, Capitalism, racism) and often with good reason. Because of the association of this cause célèbre with the often acerbic and always arrogant Clement Greenberg, formalism as an ethos is out of fashion, to the point that “clembashing” is still an activity that causes practitioners of the modality headaches even today. The contemporary painter Andrea Marie Breiling has commented that she finds herself asking (in the context of wanting viewers to see and experience with purpose) “How could I make work that sucked people in and lifted them to a higher state? A spiritual place itself and not a place of painting for painting.” Tldr- the specter of Modernist formalism is real for many a contemporary abstractionist.

While formalism begat reductionist tendencies and was certainly in vogue for a non-trivial amount of time, its dominance was not total. Note that the larger, meta-cultural question “what is Art” of which formalism is a progeny also lead to many investigations which pointed creative activity away from not only abstraction (eg Warhol) but from painting itself (eg Duchamp) on the same and similar timeline(s). In particular those of us who are instructors *must* be clear with our charges that figurative painters like Jack Levine and Romare Bearden were active and making important art during formalisms’ heady heyday, and further that the conclusion that formalism as a response to the question “what is Art” was either inevitable or the most logical response is just a silly position to take, then, or now.

It’s also worth noting that most artists who practiced “painting for painting’s sake” (or at least were celebrated by the art critical community for doing so) did so out of a commitment to a broader, cultural mission to create new ways of seeing, suited to a new world that needed to abandon outdated institutions and mores (avant garde anyone?). I would argue the cultural context of this activity is definitely part of its content, even if it was not to be considered primary.

I find Adam Simon’s review of Tom McGlynn’s work published by Two Coats of Paint (a legit source of love for painting) enlightening in the context of these considerations. Adam notes that, for the contemporary artist considering reductive forms “these basic shapes are historically weighted signifiers, no longer free of association. One cannot now make a geometric abstract painting without it also being a depiction of a geometric abstract painting.” It’s also very much worth reading what Saul Ostrow wrote (also in Two Coats) about Jeremy Gilbert Rolfe’s Paintings from 2009 to 2022 at David Richard to further flesh out the idea that no form used today can be considered bereft of “content.” BTW, these two writers don’t necessarily agree.

One of the distinctions I am quite interested in, as a way to understand artists who leverage formalism as either a generative strategy or an ends, is exemplified by the North Carolina-born painter William T. Williams. WTW is known for his process-based approach to painting that engages motifs drawn from personal memory and cultural narrative to create non-referential, abstract compositions. He is known to have said that “my art is about my experience which, by nature, makes it about other people’s experience . . . I’m trying to evoke human response. My demographic is the human arena. I hope my work is about celebration, about an affirmation of life in the face of adversity, to reaffirm that we’re human, that we’re alive, that we can celebrate existence.” I think this illustrates a very humanist, and therefore Modernist, tendency within William’s oeuvre. The Concrete Art movement, as described by the historian Werner Hartmann in this excellent Wikipedia article, summarized their ethos thusly- “Art should endeavour to give form to life itself.”

For this writer, I find the phenomenological musings of Robert Irwin of greatest influence on my approach to making work which seeks to engage the imagined viewer in a sense experience distinct of narrative and subject. This is possible or at least conceivable for Irwin, and myself, because of bracketing. Irwin also elevated questioning in his practice. For this creative, questioning- probing a form or strategy until it reveals a direction or intention- is a if not the central strategy for generating objects. If there is an example of what a practice which centers the “language” of color and shape looks like, I would offer it is Stanley Whitney’s, with his strategy of “following the painting.”

If a (revised? reformed?) formalist strategy can exist today, I think it’s clear it isn’t in the way that we are taught to use the word in academia. Jason Stopa hints as well that there is a possibility for a sub-set of the activity of painting to exist in a way that allows space for contemplation which is sort of parallel to “traditional” formalism- he calls it “self-reference.” He also sees the act of making the work as a reference to the world of ideas because the context of the activity is our very non-utopian society (I think this is very much like the way Williams approached painting). In an Instagram post (of all places) he dropped this gem (in reference to his exhibition Joy Labyrinth for which Raphael Rubenstein penned the catalog essay): “I see self-reflexiveness in painting as a means toward criticality. The utopian architecture I’m referencing in these paintings is about the impossibility to create ideal conditions, but our pursuit of idealism persists nonetheless.”

I really love the group discussion Jason put together just before the start of the pandemic with Katherine Bradford, Sharon Butler, Thomas Micchelli, and Craig Stockwell, who has this wonderful quote: “When things get real and very difficult, I need to turn to something that is sustaining. I think painting in all its forms is remarkably engaging as a thoughtful activity, as a thoughtful and physical activity. Personally, to go to the studio and have the experience of making, spending hours in this thought process, and responding to difficulties, seems so small in certain way, but it’s incredibly sustaining in a difficult time.” I don’t think Craig Stockwell would ever say he paints solely for “paintings’ sake” and I can’t think of anything else to call the impulse he describes other than a belief- faith?- that painting is valid as an activity that centers itself, full stop.

All of these words lead me to this series of thoughts, that are nothing more- or less- than the reason I am, to the amusing frustration of so many of my contemporaries, really quite comfortable referring to the object-based part of my own practice as “formalist.” Primarily, is it because, transparently, that activity, in the confines of my studio, centers form, line and color; thoughts shape my direction and words to contextualize editing decisions come after, but, in the moment, I am following the object. Further, the contemplation and reflection by an artist during creation and, later, an audience during display of the result(s) is an intentional activity that elevates and preferences the senses. The act of this contemplation and reflection is a social construct and a subject of philosophical inquiry and therefore can be both distinct of and content of the work itself. And, this act of contemplation, bracketed outside of our utilitarian social institutions, is imbued with the very spirit of the human condition and relates by default to identity, to politics, and to the striving of all people for connection and transcendence.

Awe

One of the (many) ways my community is awesome is Jean Gray, and one of the ways Jean Gray is awesome is a discussion group she’s recently started, Discourse and Dialogues. And “yes” this article is a form of endorsement, next event is 5/24 for Raleigh folks (and you can put a reminder on your calendar that they meet every 4th Wednesday). FYI, I’ll be leading the discussion this time around as we dig into what formalism can possibly mean in 2023. If you miss it, I will definitely cover the topic in a future update.

As part of participating in this group, I found out about another awesome, new organization in Raleigh that you all should be following, Small School, a new, art-based alternative educational platform. Primarily focused on lectures/discussions to start, the plan is to offer… more, down the road. Check out their site, sign up for their list, and show up for an artist talk. The one I attended with Killeen Hanson and Leslie Vigeant was amaze balls- big surprise that it drew me in with a title like How Do We Pay Attention to What We’re Paying Attention To?

Through the Discourse and Dialogues discussion group, and participation by the Small School staff, I learned about Akiko Busch, the next visiting artist, who is also an author of several books, including How to Disappear. I’m getting there… the book touches on this study by Paul K Piff and others that explores “awe” as an “emotional response to perceptually vast stimuli that defy one’s accustomed frame of reference in some domain” (generally, in specifically, experience as part of viewing art) and pro-social behavior. I’m just now beginning to dig in on this work (for the ;tldr crowd def click on the hyperlink to the recording of Paul’s talk) but the high-level take-away as the kids say these days is that the study is actual, hard science, focused on “awe felt during experiences with religion and spirituality, nature, art, and music” which often centers upon two themes “the feeling of being diminished in the presence of something greater than the self, and the motivation to be good to others.“

Anyway…

Pivot

This is a fun word to try to write about on my Art blog because we use this word all. the. time. in the business world. I’m not sure if it has a lot of meaning inside the Art world. My inclination is to say “I’m pivoting away from drawing” and hope that lands.

Regular readers know that at the beginning of the year I picked up Oblique Strategies, thinking (after learning about the project which is part of the musician Brian Eon’s visual art practice) it would fun to “draw my may” through all 100+ cards. I definitely benefitted from the activity of drawing every day. I also found I was inevitably forcing my drawing preferences (isometric cubes) into an exercise that was really meant to be a catalyst for writer’s block. I did benefit from being required to think about “why” as I began to draw I’m sure, and as an abstractionist I of course loved the unplanned element of getting an unknown prompt and responding to it. And every once in a while there were gems like below, which I really did take as a sign that there wasn’t a good conceptual reason to resist my natural drawing instincts.

And, I got some good drawings out the process, all the evidence once should need that there’s not need to make things harder than they need to be.

As time rolled on, around 70 drawings in, I began to think that maybe the exercise of forcing my practice into this kind of construct wouldn’t be as productive as, say, taking the good compositions and working on them some more as, you know, paintings. I had tried some smaller scale paintings recently (below) and that smaller scale seemed liked the first place to start.

So I picked 3 of the compositions (I had already pulled a few aside as TBC material) and am in the process of translating both compositions (via projector of course) and application strategies into some smaller scale paintings. I’ll continue to look for the right polygons to enclose them as I have with recent paintings (ergo the tape around the sketches visible in 2 of the images below).

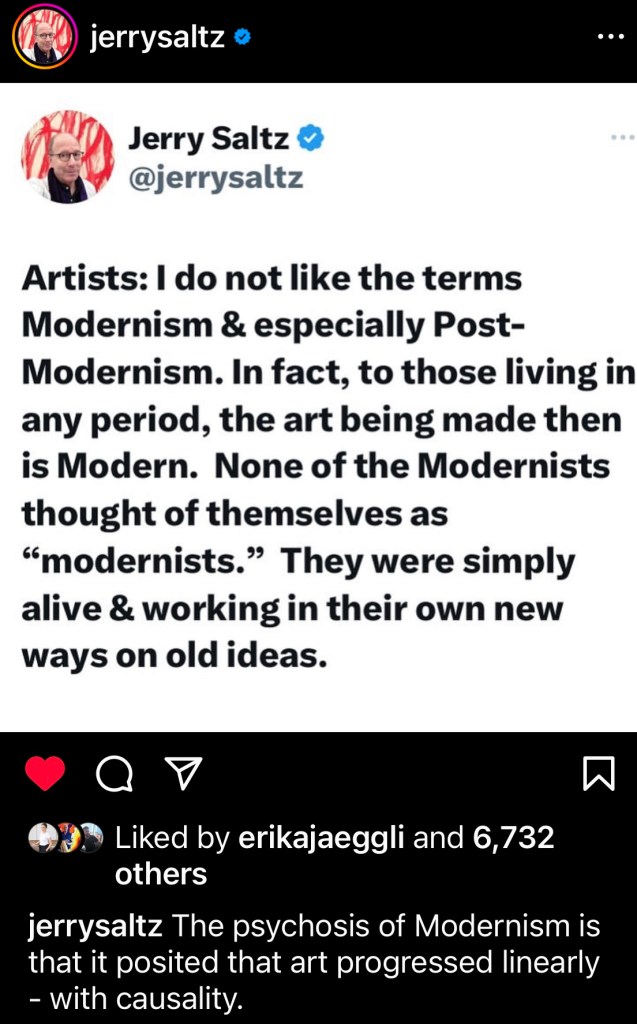

Toward

I’ve thought about the observation below several times since first seeing it on the Instagrams, as I have a good bit of loathing for academics who get hung-up on needing to be recognized as post-modern. Interestingly, I first saw the post right after giving the final lecture for my color class recently. In it, I covered artists who make color their primary subject. I started by telling them the story of Western Art that we were all taught (the story, and that it is one- which Mr Saltz points to in his comment below his repost of a Tweet). Art moves “forward.” As I’ve noted, I don’t hold to the notion that Art has anywhere to go. AND, I am sensitive to the reality that I feel, about the moment that is 2023, probably very similar to many creatives and intellectuals we would label Modernist, that I am living in a moment that necessitates change and that our past socio-economic systems and norms will not serve in the world as it is developing. One can move toward a goal without having to call the direction of movement “forward” or note it as “linear,” or attribute casualty or necessity for the movement. BTW, Jerry’s last book Art is Life is nice collection of essays from several decades.

I mentioned in my last post that I had accomplished- moved “toward”- my goal of curating an exhibit. ExtraSpectral is now open to the public, at the Truist Gallery which is on the 1st floor of the Durham Art Council building (but operated by Durham Art Guild) at 120 Morris St in downtown Durham- until June 6. Public hours are Monday – Saturday, 9:00AM-9:00PM, and Sundays, 1:00PM-6:00PM. BTW, a couple of the artists gave a talk during a soft opening which you can view on YouTube. I learned quite a bit from the process, as hoped.

I am also moving toward a large, finished painting that has been in progress for a minute, if one considers it’s effectively the 3rd iteration of an idea.

Curating

So I will be the first to grant that in this day and age creatives sometimes refer to curating in the context of their Instagram feed. I don’t know if my feed comes off as “curated” and I am very intentional about it. I post every 4 days (3 posts) with every third one featuring other creatives.

Curating also obviously refers to organizing an exhibition. When I first began studying art in an academic setting, this activity was reserved for art historians and professionals involved in the critical discourse. I feel like that has shifted over the last decade, possibly sooner (which I wouldn’t know because of the long break I took in practicing) towards artists themselves organizing and curating exhibits.

I got back into this game to create culture- to not only make but teach about, talk about and write about creative activity that makes this life more. No there’s not a word missing in that sentence. This reason and the general context I outlined above is why I made a commitment to trying my hand at curating in 2023, and I was fortunate to have a proposal accepted by the Durham Art Guild for a show this spring, which is titled Extra Spectral.

Extra-spectral colors cannot be evoked with a single wavelength of light, rather, they can only be seen and created by a combination of them, so you won’t see them in the fantastical prismic illusion we call a rainbow. The exhibit highlights artists Jane Cheek, Jerstin Crosby, Zach Storm, Tonya Solley Thornton and Leif Zikade. All five ask color to play a primary role in drawing audiences into their work, colors in most cases that are “extra” in the recent, common parlance. This is where their commonality ends.

There is a pre-opening and artist talk on 4/6 that you can register to attend and otherwise I hope to see many of you on Third Friday in Durham (gallery will keep normal hours including recognizing Monday the high holy day of museums by being closed).

BTW, I was also successful as part of this goal in getting another show programmed at several venues, this one including my work. Open Source will open this summer at LUMP project space and Sertoma Art Center.

Habituation

Trying to pay attention is part of my practice– to the work, to the art world, to the overlap of late capitalism with it all. Plenty of times, the universe serves me up something and occasionally my practice includes words, too, so, here we are.

Recently I was reading an article one of my professional contacts posted on LinkedIn from Harvard Business Review about the value of changing how you are looking at things as a catalyst for thinking differently (I know, right- of course I’m clicking on that topic). In it Adam Brandenburger notes, of thinking differently, that it can be driven by learning to see differently, which hooked me immediately because of my personal journey and that word contradiction I’m always on about.

The thrust of the story is about people like Robert Taylor, who invented Softsoap after he saw how goopy bar soap became after a few uses, the main point being that “we can think of the effort not just to think differently, but also to see differently, as a way of countering our built-in tendency to habituate, to sink in to the familiar way of seeing and experiencing. One way in which great artists, entrepreneurs, and creators of all kinds come up with the insights that enable them to change the world is that, very literally, they do not see the way most of us do. Their methods teach us that by seeing differently, we can end up seeing what no one else has yet seen. This is how the future is built.”

(Ideas and discussion of what building and specifically building the/a future which were already developing in my mind aside, stay tuned…) I. Love. This, and not because I’m an entrepreneur or buy into America’s cult of personality around them. The article really got me thinking about habituation as it pertains to the visual arts (it certainly is well-trodden territory in the sciences), at least for creatives that spend time thinking about how their work is physically perceived by the audience (I would argue that my maximalist “remixes” are anti-habituation). It appears the Architectual (A)cademy has given this topic some attention but the Art critical community? Guess the thing I got served is the motivation to move from passive observation to active engagement…